A Panther in Africa visits Sacramento

Charlotte Hill O’Neal AKA Mama C, co-chair of the Kansas City Branch of the Black Panther Party and Director of the United African Alliance Community Center in Tanzania visits with Ethnic Studies teachers at Casa Masayuki in Sacramento, California to share Ancestral Veneration rituals. During her travels to the United States Mumia Abu Jamal sent this audio welcome.

Charlotte Hill O’Neal AKA Mama C, co-chair of the Kansas City Branch of the Black Panther Party and Director of the United African Alliance Community Center in Tanzania visits with Ethnic Studies teachers at Casa Masayuki in Sacramento, California to share Ancestral Veneration rituals. During her travels to the United States Mumia Abu Jamal sent this audio welcome.

See the story of her life and work in the documentary “A Panther in Africa.”

Ethnic Studies Beyond the Classroom

by Estabaliz Sanchez

Teaching students Ethnic Studies during their freshman year has allowed me to see the growth and impact the class can make in only four short years For some students, I see a transformation in their advocacy and leadership in right away, but for others I see it evolve over time. Both outcomes bring me so much joy! I have the amazing privilege seeing their growth as community leaders. What is most impactful is that I see how Ethnic Studies can create leadership in students beyond the classroom. I would like to share some of the ways our school site has been transformed since the implementation of Ethnic Studies at our site.

The final project in Ethnic Studies is the Youth Participatory Action Research Plan (YPAR). Students use their knowledge learned in Ethnic Studies to see how they can enact change in our school site. Student research, collect data, and interview staff and students based on their research topic. Some of these research questions are shown in the picture below:

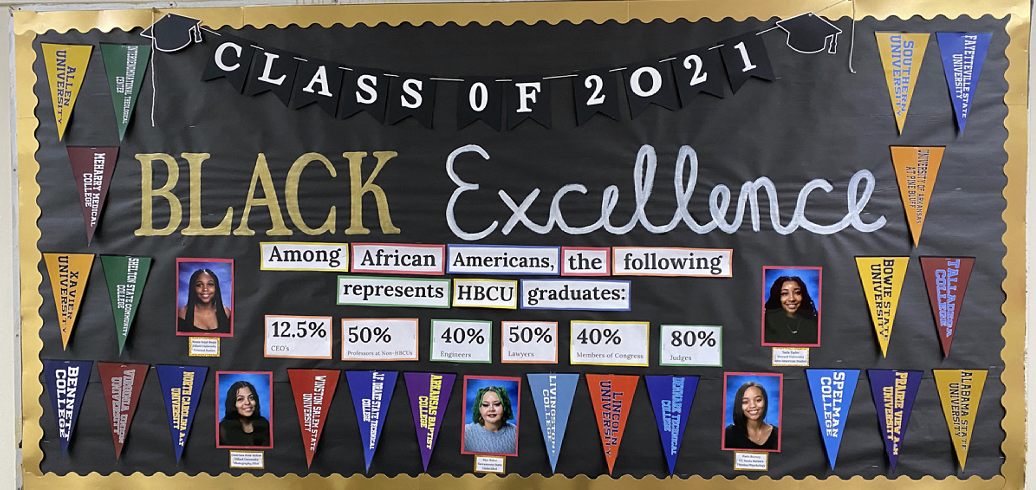

These YPARs have resulted in true systemic change at our school site. For example, we invited a panel of Black students to speak their truth during a staff professional development about their experiences in the school and some of the injustices they face. This was a big wake-up call for our staff which inspired the push-in model led by our intervention team. We have made our AVID program geared towards enacting supports for our first-generation college students coming out of our program. We found what we’ve always believed and that is that representation matters. Students deserve and now have AVID teachers that look like them with similar college experiences and challenges. In addition, three AVID seniors advocated for HBCUs to be represented in our AVID program. Not only did they also apply themselves, but they are all currently attending HBCUs.

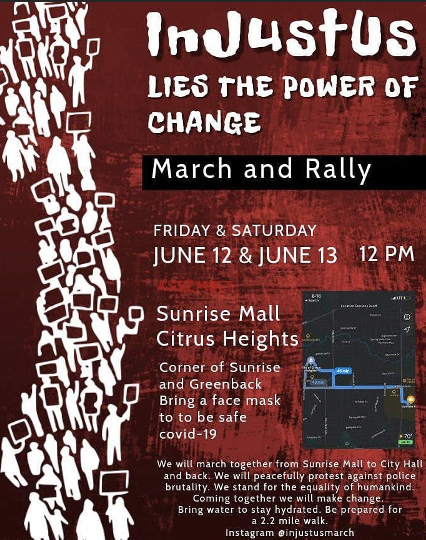

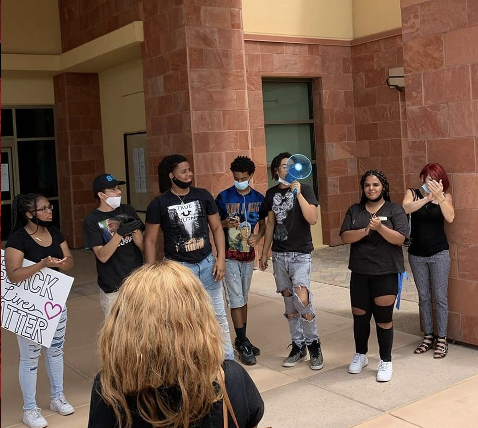

In summer of 2020, two students, Jordon Modkins and Asia Morris, led a Black Lives Matter march in Citrus Heights after seeing that there was a lack of support from the community after the death of George Floyd. Both students were interviewed by our school district, San Juan Unified. One of the leaders noted that her interest in advocacy was rooted in our Ethnic Studies class. The student activists asked another colleague and me to assist in the logistics of the march, but to their excitement, many other staff members supported with resources and marched as well. In fact, dozens of students, parents, community members, and teachers showed up to support our students and the movement. You can watch the video here.

In my 5 years of teaching this course, I have grown as an educator and human being. There are so many more examples of the impact of Ethnic Studies at our site that I could go on and on! From the in-class discussions we have where students share their experiences and draw connections, to the content in class, to seeing students working on their YPAR projects knowing that they will have their voice heard at our site. I have had the amazing opportunity to hear the narrative and experiences our students bring into the class and also see how they begin to see the world around them. They see the humanity in each other and also validate their experiences. My main goal for the course has been to build empathy and action-oriented work to change our community. Our students continue to meet that standard year after year. Their resilience turns into advocacy and their advocacy into inspiration for others. And now, even with the most challenging years we have faced as educators, the work continues. Ethnic Studies will continue to impact beyond the classroom and into our site and communities. Our students will be agents of change wherever they go. Ethnic Studies truly is transformative work.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Estibaliz Sanchez, Ethnic Studies & AVID I | AP Psychology; AVID coordinator/AVID Club; Educational Leaders Club; LGBTQ+ Club; Latino Dreams Club; STEAMS club; San Juan High School

What' I’ve Learned as an Ethnic Studies Educator

by Estibaliz Sanchez

During my undergrad at Sacramento State, I joined the Student California Teachers Association (SCTA) and learned about so many facets of education, but what it did most was solidify my desire to become a teacher. I received many opportunities to learn from amazing educators like NEA Teacher Excellence award recipient of 2014, Kimberley Gilles. She had such a huge impact in my teaching career. She gave a profound presentation on her Matthew Shepard unit taking a huge risk teaching what some people may call “controversial” material in school site that was not very receptive to LGBTQ+ content in the classroom. I always knew social justice was the foundation of my teaching, but once I saw what it looked like in a classroom, it made me fearless. I realized the potential impact my classroom could have in creating a safe space that allows students to be their authentic and true selves in the community without fear. Ethnic Studies presents that transformative work in the classroom.

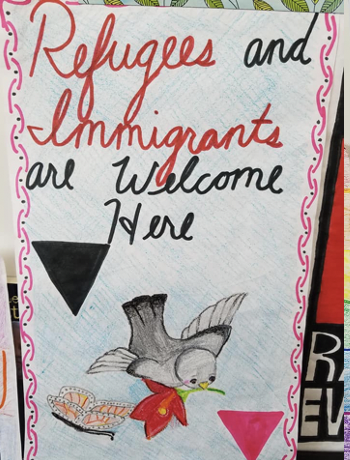

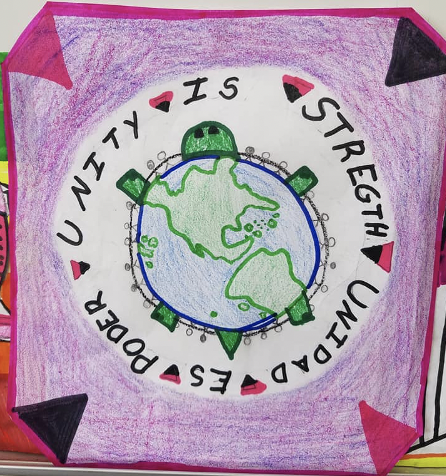

The first advice I can give an educator ready for this work, is to have showcase social justice in the classroom. Sending positive and affirming messages to students on our walls is an initial step in building the strong relationships that allow students to be academic risk takers. My mission during my first year teaching was to gather safe space posters from rallies I attended, teacher conferences, and anything I could find on the internet. I began to take a lot of pride in the aesthetic of my room and even I began to feel a warm welcome as I walked into my room every morning.

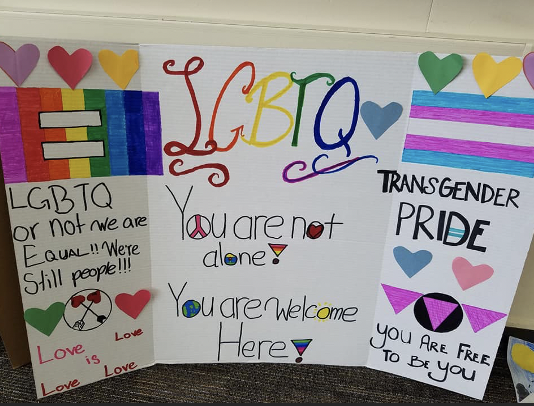

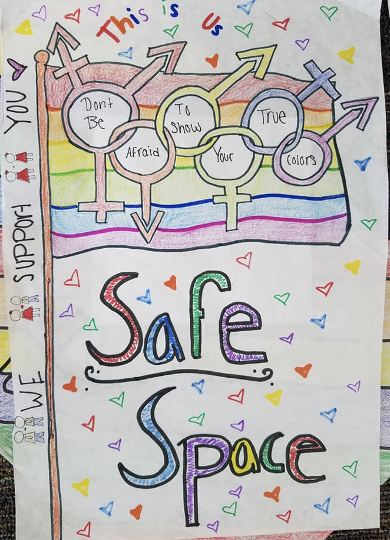

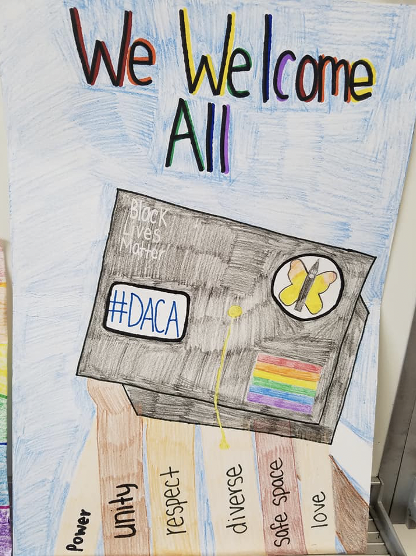

As we moved along the school year in Ethnic Studies, I made every final assessment of each unit into an action-oriented project. From writing to our local state senators about the family separation along the border, creating online petitions to promote statues of POC, LGBTQ+, or other intersectional leaders, to writing protest music as a form of resistance and healing. As I approached my LGBTQ+ history unit I wanted to create connections that would build on allowing students to stand up to bullying. This is where I started to make connections from my time in SCTA and the work of Mrs. Gilles. Students dove deep into the meaning of the pride flag and other flags of LGBTQ+ identities. This included learning about the dark history behind the inverted triangle and how the community reclaimed it as a way to promote safe spaces. Students also learned the language used in various safe space posters that were provided online by the CTA.

Students began to realize that as cool as the posters looked, the message through the art was much deeper. We looked around my room to analyze varios posters I had and then reflected on our own school make-up. ‘Why don’t we have more safe space posters around our school, Ms. Sanchez?’ And there it was. The final assessment for our LGBTQ+ unit, safe space posters.

I gave students basic directions because art cannot be confined by too much structure. Students were directed to be intentional about the symbolism used in their creation including color and size. I told them our goal was to create safe space posters for teachers to be able to put in their classrooms. This gave our project meaning. These posters were going to make our entire school into a safe space. Some students were skeptical that their teachers were going to put their posters in their classrooms, but at the same time, it encouraged students to be very detailed in their work. Behind each poster, students wrote a one-page explanation and analysis of the message, purpose, and meaning behind their poster so the teacher who chose their poster would know more about the work put into them.

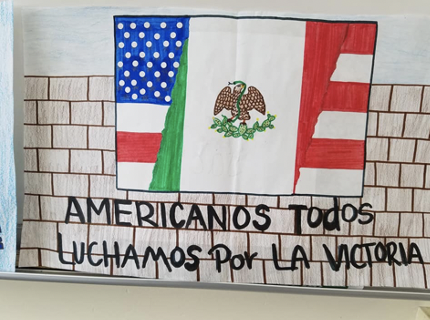

As we began our work, I noticed students who were uncomfortable at the beginning of our LGBTQ+ unit choose to create an LGBTQ+ safe space poster. I could see their empathy building and as they became more aware of how marginalized groups like LGBTQ+ students needed a safe space. Other students chose to send messages to our EL, refugee, immigrant communities, and our Black students to show they matter. Others chose to design inclusive messages for our students with disabilities.

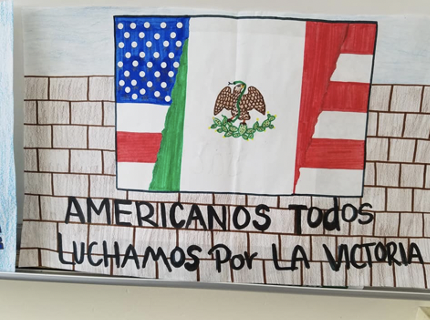

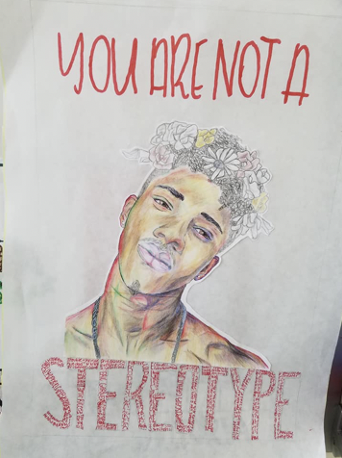

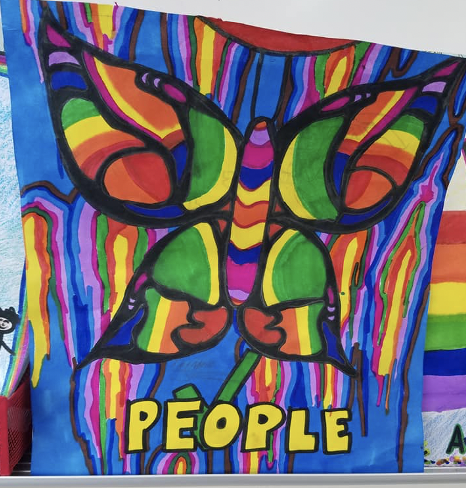

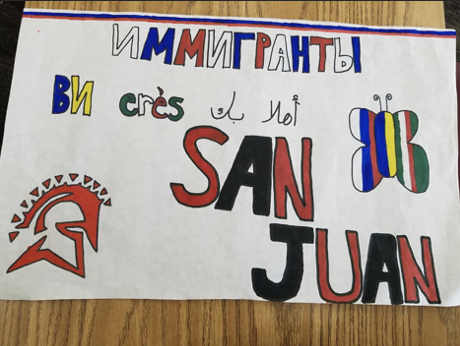

Here are some examples of their work:

The final step was to continue placing students in leadership roles and to see the impact of their work on our site. Students were invited to come to our staff meeting and showcase their work while explaining the value of safe space posters in the classroom. I also presented to my colleagues on how having a student’s safe space poster in their classroom is an instant relationship builder for a student that they may have in their class next school year. My colleagues were excited to receive the work of our students. But what was more impactful was students seeing their work displayed in different classrooms, the principal’s office, the library, and counseling office. They saw their safe space posters change the culture of our school site. Now this school was theirs. I have been doing this unit for 4 years, and every year I get former students reflect on the pride in their work while in Ethnic Studies but I also see that our site still has their posters up many years later. A safe and welcoming space for all was made at our site because of the voice and leardership of our young scholars.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Estibaliz Sanchez, Ethnic Studies & AVID I | AP Psychology; AVID coordinator/AVID Club; Educational Leaders Club; LGBTQ+ Club; Latino Dreams Club; STEAMS club; San Juan High School

Co-Opting Language

By Tony Diaz, El Librotraficante

English is not intended to work the same way for them as it does for us.

The rulers use it to create rules to maintain their rule.

The colonizers’ language came first to steal and contract our land, imaginations, Our People. It doesn't matter if it was the british king or the spanish king they were monarchs. Those words came to raze Our Libraries, Our Art, Our Culture. And then they would use the kings tongue to declare us illiterate and declare our land their land and then create the documents that would undocument us.

That racket continues. It is in the user agreements we are tricked, conned, forced, bribed into signing every hour of every day. English is brutally honest, but we are all too brutalized. We numbly click all the user agreements. We are boxed into their perspectives via petty barrages every day.

Just to give you an example of how this hustle has expanded over generations think about what those early invaders are titled. In school, during the half hour that the state sanctions material about Meso America, these early high way robbers are called the Spanish Conquistadores.

They created a racket that would continue for half of millennia which was an update of the monarchies of europe. Europeans were expert at manipulating feuding tribes because that is they were. Europe teemed with tribes that not get along over centuries that turned into imperial armies then fought, manipulated each other, stole each other's riches. Their modus operandi was violence when you didn't have your way, resorting to the most barbaric nasty violence known to man.

cortes was no genius. He was mediocre. Why else would he get into a boat and float into uncertainty? His hopes for wealth, power, and fame were stunted in spain. He could not compete with the 1%. He was good at violence, but not enough to conquer the surrounding more cunning, more violent monarchs. kortez was a master of violent arts for his master-the king who engendered universes called universities to educate subjects so subjects made him the center of that universe.

cortez showed flashes of brilliant violence. he was cunning he was loud. Surely, the king was more than happy to gamble with cortes’s life to get him far, far, far away from the court. And maybe, just maybe, the gamble might pay off.

I know all this because I am a Librotraficante. I grew up as a translator. I understand how language is weaponized against us and against others. I also know it is powerful. It helps us survive and thrive. When I earned my Master of Fine Arts I mastered the masters english, but I rejected masters.

I am liberating english to finish my Book.

This is not a book with a lowercase “b” because it is not simply a consumer product meant to make another buck, which means it's not written following the rules and regulations and myths of the corporate publishing world which simply cranks out colonizer fantasies or manuals for rules for the rulers to maintain their rule in the fine print of their fine art.

This is a Book with a capital “B” because we are co-opting English, infusing it with Community Cultural Capital to liberate Our Voices, Our Art, Our Culture, and freeing the most potent of Community Cultural Capital-our stories, our imagination, Nuestra Palabra.

I type this Book in time for the 10th Anniversary of the Librotraficante Caravan that smuggled back into Arizona the books from the Mexican American Studies Curriculum banned by right-wing Republican politicians. It is true, our History and Culture were banned during our lifetime. And Arizona officials have yet to apologize or make amends. This Book is a reckoning because there are forces that strive to prevent us from acquiring knowledge. We must school them.

I am typing this in time for the 25th anniversary of Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say, which I founded in 1998 in the party hall of Chapultepec Restaurant.

I write this 500 years after the Spanish pirates invaded and stole the land of the Mexica and razed their libraries, temples and burned their books and art.

The epigram to Our History is 500 years long. Now, we begin to tell Our Story. Our Terms on Our Terms.

And the time is now.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Writer, activist, and professor Tony Diaz, El Librotraficante, was the first Chicano to earn a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the University of Houston Creative Writing Program. He earned his bachelor's degree in Communications from De Paul University in Chicago. Diaz is currently a professor of Mexican American Literature and Rhetorical Analysis in Houston, Texas.

Music, Solidarity, Resilience, and Hope in the Classroom

by Estibaliz Sanchez

I knew becoming an Ethnic Studies educator I had to be aware that the work is not easy or comfortable. I became a teacher after the 2016 elections and the worst year of police brutality against the Black community. One thing I knew to be true was that my students were well aware of the world around us. I didn’t have to explain much but to just say their names: Philando Castille, Trayvon Martin, Alton Sterling, etc. Unfortunately, their experience also had them wondering, ‘Am I next?’ This is what gives Ethnic Studies its essence and soul. This class allows students to recognize that they have power in creating change. This class connects students with their experiences and community and then seeks to build empathy and solidarity.

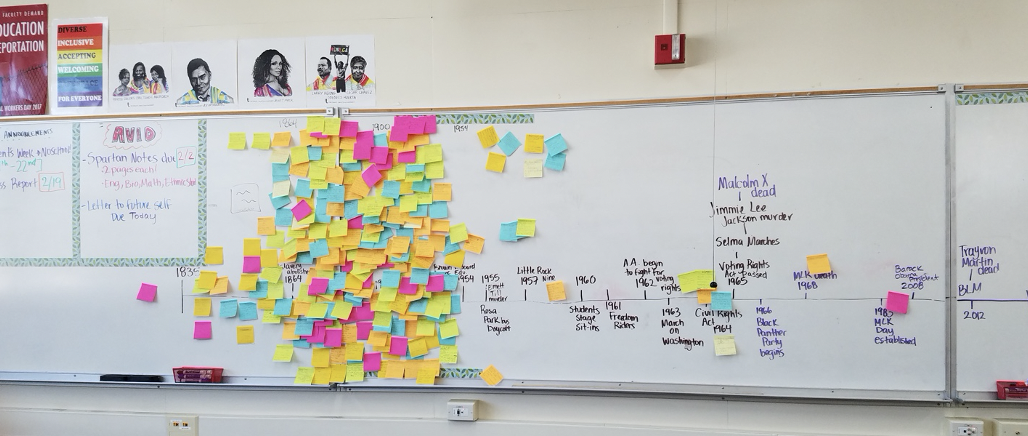

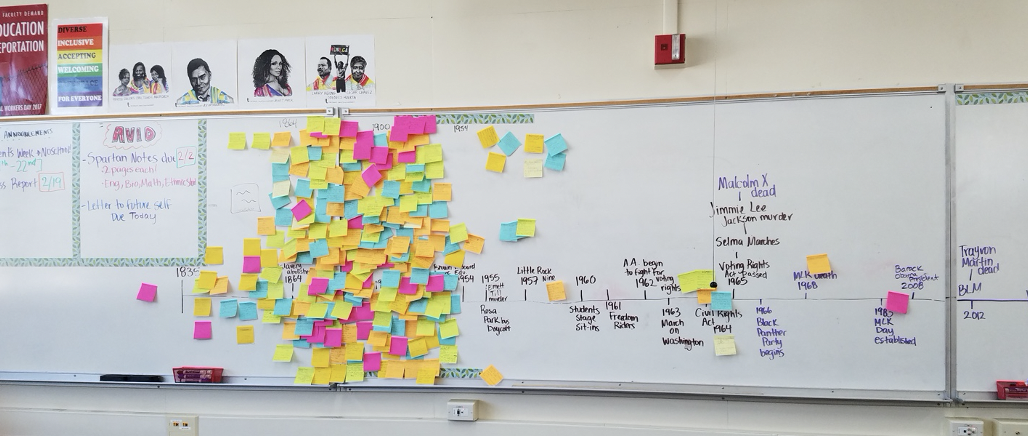

At the same time, I was doing a pre-assessment of their knowledge in civil rights history and what I found was truly alarming; their knowledge of civil rights was skewed by years prior of making civil rights history a lesson or two. From not being able to name more than one civil rights leader to not understanding the chronological order of events; I knew I had foundational work to do. I needed to find a way to make the historical connections to what my students were experiencing in their current world. Yet, the age-old dilemma of a history teacher is, ‘How am I going to pack in this content in a couple of weeks?’ Realistically, there was no way. I needed to think outside the box that places history teachers as the teacher who makes you take pages of notes while they lecture for days on end. In my class, there is always music playing and this is where inspiration hit.. feel this is an important piece in my pedagogy as an educator, from a cultural standpoint, anytime my mom wanted to get down to business and clean the house music was essential for the work. I decided to use music to guide this unit.

I spent days researching protest music by Black artists that would encapsulate each decade leading up to today. I wanted to showcase mainstream artists who used their platform to send the message that Black Lives Matter. Meanwhile, I created mini-lessons in between to fill in the knowledge gaps needed for historical context. I prefaced our music by explaining the two forms of protest music we would be analyzing. Rhetorical protest music aims to be very straightforward in its political message, sometimes even noting the artists tone is serious, frustrated, or disillusioned. Magnetic protest music seeks unity and aims to have its audience commit to the social movement.

First, was Billie Holiday performing on National TV her song “Strange Fruit.” I printed out the lyrics for my students so we could annotate line by line to gain a better context. By the end of our listening, I asked my students ‘What is the Strange Fruit Billie is singing about?’ No one could answer. I then displayed an interactive map from Plain Talk History that showed lynching from 1848 to today. This was the strange fruit. Students were stunned. Silence and gasps filled the room. I passed around sticky notes and had students research 3 people who were lynched at any year and write their names down. We had to say their names. This was not just any lesson. This was an act of remembrance and honor for those lives lost.

When listening to Fight the Power, students were prefaced by learning about the Black Panther Party to understand the imagery in Public Enemy’s music video. We went along the decades and listened to: Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye, Public Enemy, Tupac, Kendrick Lamar, Prince, Beyoncé, J. Cole. To really understand how the message has always been there, Black Lives Matter. Then we ready to understand that commercial Black Artist have been using storytelling to raise awareness on civil rights issues in the Black community. My students were starting to connect the pieces.

Student’s began analyzing song lyrics and classifying them as rhetorical or magnetic. They also used sticky notes to summarize each artist’s message. They started to see the power in activism through music. Each performance we watched, I could notice students were seeing the magnitude of how artists were risking their careers and lives to talk about issues in their community. But now, I had to find a way to end our analysis into restorative and healing work for them.

As we ended the unit, I needed to allow space for students to look within their own experiences and communities to create their own protest music. As is with art, I did not give many parameters other than they had to write their own analysis on their music and decide if their protest song was rhetorical or magnetic. They also had to be prepared to share their piece to the class. I have done this unit for 5 years now and it continues to be my favorite day in class. Students write music ranging from BLM. LGTBQ+ rights, Women’s Rights, Bullying, School to Prison Pipeline, Immigration, etc. Here are some examples:

We were able to process a lot on this day. The room was filled with tears, applause, and best of all, a safe space for healing. Students to this day, come to my room and tell me how that was one of their favorite units. What I learned from them is that learning in the classroom can turn into a moment of healing. That we can turn these dark moments in history into resilience and solidarity. Seeing young brilliant students in class have academic conversations about J. Cole’s song “Be Free” and drawing connections to how his anger and disillusionment is similar to Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” are moments where I know Ethnic Studies goes beyond a lesson, primary source, or handout. Ethnic Studies is resilience, solidarity, and hope.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Estibaliz Sanchez, Ethnic Studies & AVID I | AP Psychology; AVID coordinator/AVID Club; Educational Leaders Club; LGBTQ+ Club; Latino Dreams Club; STEAMS club; San Juan High School

Ending Book Deserts

By Tony Diaz, El Librotraficante

We know what book deserts look like. We drive through them all the time, on the way to the mall.

Pick any major city with a large Mexican American population, and you will see that book deserts engulf our communities.

Some folks pretend to care or feign a desire to learn how to eliminate book deserts. No, those folks have already blamed our own community for creating the book desert forged by the neglect and avarice of corporate publishing, corporate bookstores, corporate media, and corporate english.

What is corporate english? This is the current evolution of the king’s english that forms the rules created by the rulers to maintain their rule.

Librotraficantes are expert at hacking it. Our first job as kids is translating the outside world into Spanish for our parents. We eliminated the king’s lisp from the king’s spanish. We created Spanglish. Whereas corporate english captures the imagination by day. By night, Librotraficantes liberate words.

corporate english forces our minds to be distracted in an essay by the main topic. Let’s call that the king’s topic, which in this case would be: why have the Latinx allowed the barrio to become engulfed in a book desert?

No. we won’t be sentenced to that racket.

The real question is how our community can profoundly understand our power, cultivate that power, and then unite to accelerate our community cultural capital.

corporate english does not mandate a book dessert. But, let’s get something clear. the erasure of our art, history, and culture, is written in policy, legislation, and coded into practice.

I only have to remind you that just a few years ago, Arizona right-wing officials banned Mexican American Studies. The Librotraficantes organized the 2012 Librotraficante Caravan to smuggle back into Tucson the books from the outlawed MAS Curriculum. Our community united to overturn that racist law. However, to any just-minded, reasonable person, I do not have to explain how blatantly discriminatory laws play a role in erasing our Culture which leads to book deserts.

This is obvious.

A more subtle approach is based on the dots of corporate graphs forecasting their profits, dodging our neighborhoods until it is time to gentrify our abuelo’s house. Those dots on corporate margins code book deserts, forge the self-fulfilling prophecy that our gente do not buy books, do not want books. Those dots add up to the language that describes smart, sound, safe investment in any other community but ours.

We cannot employ the corporate language or practices that lead to the user agreements that create book deserts in our community.

And on October 1, 2021, the Librotraficantes, Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say celebrate with The Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, under the leadership of its Director, Cristina Balli, launching their Latino Bookstore and Gift Shop, becoming the only-THE ONLY-book store on the West Side of San Antonio.

This bookstore will not follow corporate tactics of intellectual gentrification.

The Guadalupe’s Latino Bookstore is built on and creates more Community Cultural Capital. The books on our shelves are not just products. They are not just blocks of wood. Each curated book represents the deep history of the center, art created in the center, San Antonio, Tejas, and our gente’s contributions.

Here are just a few ways that we defy the king’s corporate english that sentences us to book deserts.

We are investing, literally, figuratively, and artistically in our community.

We will focus on Texas Latino writers, Mexican American Studies, Chicanx Scholars, and icons. You won’t find these terms on corporate pamphlets or even in the search history of the computers of corporate executives.

Our bookstore has a Padrino and a Madrina: Chicano Studies scholar Dr. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto is our Literary Pardino; we will have signed copies of the book he co-edited: "Recovering The U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage, Volume VII" published by Arte Público Press based in Houston; and Texas Poet Laureate Carmen Tafolla is our Madrina. We will feature her new children's book “The Last Butterfly,” published by FlowerSong Press based in the Rio Grande Valley. Corporations don’t have padrinos or familia.

Here is a dose of Community Cultural Capital in action: Our launch will feature our padrinos and also the national launch of Dr. Roberto Cintli Rodriguez’s new book: “Writing 50 Years más o menos Amongst the Gringos,” published by Aztlan Libre Press.

Dr. Cintli is from Tucson. His books were among the over 80+ titles that were part of the Mexican American Studies Curriculum outlawed by Arizona officials. His new book is published by Juan Tejeda and Anisa Onofre at Aztlan Libre Press, based in San Antonio since 2009. And I will serve as Literary Curator of the Guadalupe’s Latino Bookstore. Tucson, San Antonio, and Houston are uniting to erase a book desert and to ensure that our gente are never kept from our art, history, and cultura.

I am proud to serve as the Literary Curator for the Guadalupe’s Latino Bookstore. I am touched that they are trying to make an honest man out of this Librotraficante. Perhaps, we will no longer have to smuggle our history, art, and culture into the hands of our community. I hope not. But you can bet, the moment we have to, we are ready, and we are damn good at it.

Links/Resources:

Ending a Book Desert Announcing a New Latino Bookstore (VIDEO)

Opening Oct. 1, the bookstore will offer book selections that are curated by writer, activist, and professor Tony Diaz and focus on Texas Latino writers, Mexican American studies, and Chicano scholars and community.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Writer, activist, and professor Tony Diaz, El Librotraficante, was the first Chicano to earn a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the University of Houston Creative Writing Program. He earned his bachelor's degree in Communications from De Paul University in Chicago. Diaz is currently a professor of Mexican American Literature and Rhetorical Analysis in Houston, Texas.

Where do I come from? Family ties in San Jose, Salt Lake City, and Estipac

by Izamar Ortiz-González

Where do I come from? Families ties in San Jose, Salt Lake City, and Estipac

Who are we? Where do we come from? Where am I? Where am I going? These are the primary guiding questions from Our Stories in Our Voices.

My answers are tied to the decisions my father made in his youth. I would not be in Sacramento; I would not be pursuing my Ph.D. if my father, Ernesto Ortiz, had not made the choice to leave his small town of Estipac, Jalisco, Mexico, in 1977.

At fourteen years old, my father left Esipac Jalisco to pursue more opportunities. You ask him now, and he will say, “The youth back then went to the North.” He was the second youngest out of ten children. His father, my grandfather Papá Macario, was retired at this point. Once the head of the Corcuera Hacienda, he had accumulated land and houses and distributed these amongst his oldest sons. By the time Ernesto, my father, and Antonio had been born, he only had the new house on the Loma to give them upon his death. Given that my father only passed sixth grade a puros panzasos, by the teacher’s hammering stick, at last, the school was not the path he chose. While his younger brother decided to stay, my father chose el Norte, North.

He was 17 years old, and he embarked on the journey with two older boys Nabor and Pablo. Years later, he would find out that Nabor was the older first cousin of the woman that became my mother. But I digress.

The coyote took my father from Estipac to Salt Lake City, Utah. There he worked in a hotel washing dishes. He didn’t like Salt Lake City in the 1970s. Back then, he only had 30 minutes of Spanish music on Sundays. He lived in an apartment with five other men. After two years, he headed to San Jose, California, to reconnect with three older brothers he didn’t know in his childhood.

The Rise of Silicon Valley

In the 1980’s San Jose, California, was still nestled between Agriculture fields. Cupertino, home of Apple, was just ten miles from San Jose but this fact did not become important until much later.

In San Jose he found a home; he carries with him more so than Estipac. He reconnected with his older brothers and became a role model to his younger nephews and nieces, children of his oldest sister Chepa— we call them the Borceguines.

The rise of Silicone Valley shaped my father’s and his nephew’s lives. He and his nephews started- as many did back then- picking up tomatoes. Once these were sold, they became the popular swat meat that many of us remember going to on weekends. The Ortiz and Borceguines were the families that were part of a larger Latinx community cleaning schools and office buildings.

The Borceguines built a reputation among companies and they eventually created a custodian/cleaning business and earned their contracts with schools and office buildings in downtown San Jose. They had no middle man and were able to choose where they wanted to work.

One of the Borceguin brothers was fortunate to have met Carmen. Carmen’s family had not crossed the border— the border crossed her family. Carmen knew how to navigate specific laws and systems in San Jose and, because of this knowledge, the Borceguin brothers were the first in the Ortiz family to own land in San Jose. The knowledge Carmen shared help my whole family. They were able to purchase these homes before the rise of Silicon Valley. They are proud of this feat to this day.

At this point he was married to my mother and had my twin sister and me. My father started working for the “electronica”— an IBM factory. Because of this, we grew up with the leftover IBM and Apple computers that were thrown away. I never figured out how, but my father managed to fix them, and we played solitaire on these computers. The screens would switch back and forth between green and black screens. We loved using the art feature to draw.

However, the rise of Silicone Valley meant that by 1997 my father was given a choice. My parents wanted to expand the family. It was time for a house. However, the homes in San Jose they qualified for were not neighborhoods in which my mother wanted to raise her children.

My father’s younger nephews, the children of his oldest two brothers Ramon and Carlos, Macaria and Teresa, had joined the Ortiz and Borceguin in San Jose. With them came more people from Estipac Jalisco. However, with Silicon Valley’s rising costs of living, a second option opened for Ortiz, Borceguin, and the rest of Estipac Jalisco: Salt Lake City, Utah.

Salt Lake City, Utah, the new mecca.

Even though in the 1970s my father and his cousin had left the city to push forth towards San Jose in California, not everyone from Estipac left. Some fell in love with the hills that surrounded the city; perhaps it reminded them of home. Estipac is nestled between hills all around.

Those that stayed behind paved the way for those who could not stay in San Jose anymore. The late 1990s resulted in a large exodus by my family’s extended family. Those that wanted houses, those that wanted more opportunities, went to Salt Lake City. In the late 1990s our families moved to Utah and joined the service industry there.

My mother’s youngest siblings bypassed San Jose altogether and headed straight to Salt Lake City. So when we visit our family there, it is not uncommon for my father to run into an old friend from Estipac working at a Denny’s.

My family was the exception. My father had a cousin that happened to live in Tracey, California. It was a smaller town back then, suburban and surrounded by ranches. What they could not afford in San Jose got them a suburban neighborhood in Tracey, surrounded by retirees. My mom liked that. My dad liked that it was a corner house. This house still haunts me to this day, but that is another story for another day.

Estipac

When I was 25, I went on a short trip to Estipac by myself. By this time, the town suffered from years of neglect from the government. The residents paid taxes but Estipac itself did not reap any benefits. However, there was a new little restaurant by one of the main avenues into the town. This street used to be the outmost edge of the city during my parent’s youth. The restaurant is called Viki’s.

Viki’s sold hamburgers, chicken wings, pizza, and anything else you might find at a fast-food restaurant in the USA but with top-quality ingredients. You knew your patty was actual meat and your potatoes came seasoned with more than just salt.

Walking into Viki’s, three portraits surprised me. They had three skylines of three cities in the United States. Chicago was there, San Jose was there, and I thought I would see Los Angeles or New York City, but instead, they had Salt Lake City.

This was 2015. By then, the people who did move up north, skipped San Jose and headed to Salt Lake City. But by 2015, most people in Estipac did not leave; they could make a good living in Jalisco. This small restaurant in Estipac carries the history of migration patterns of its people connecting San Jose and Salt Lake City.

Conclusion

My father’s story gives a glimpse of the history of the migration ties that connect communities in Mexico, California, and Uath. To understand that story, it’s important not to lose sight of the fact that it is made up of thousands of families’ stories, and that these stories are small intricate fibers that form the larger tapestry of what it means to be us.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Izamar Ortiz-González is a daughter of immigrant parents. This experience thought her to navigate multiple narratives at school and at home. Bridging the gap between these narratives has been her goal throughout her life as a teacher, organizer and student. She double majored in International Relations and Spanish for her BA at UC Davis. She received her single subject teaching credential and Masters of Arts in Education from Loyola Marymount University. She spent six years as a public school teacher in Sacramento, California. She organizes with other educators through the Association of Raza Educators.

666 Laws

By Tony Diaz

I am writing this the day 666 laws go into effect in Texas- giving it the title of the most far-right state of the Union.

Of course, metaphors are forced confessions. So the number 666 is appropriate. Some of the laws are so evil that I suspect the devil has self deported from Texas. Of course, we activists are used to the heat. So although some of this may seem new, it is clear to we community organizers on the ground that this is a reboot of past oppression. Texas is always behind the times. Retro-fashion is cool, retro-racism is not cool.

I’m not going to go over every single one of these laws. I don’t even have time to provide a “top ten worst laws” list. There is one specific law that demands our attention.

Texas’s right wing Republicans, as in other states, have implemented their own “Anti-Critical Race Theory Law.” I hate to repeat that name because it plays into the right wing strategy of misinformation. This law should be called the “Anti-Black Lives Matter Law” or the “Anti-George Floyd Era Law” because this law is intended to prevent and intimidate educators from talking about the structural racism exposed during that movement. Notice that news about the anti-Critical Race Theory campaigns picked up steam as more and more confederate statues were being taken down across the country. CRT misinformation has now dominated the news.

The Anti-CRT movement is a repurposing of past oppression. I don’t mean in general. I have receipts.

You see, I am a Librotraficante. You can translate that into English as Book Trafficker.

I clearly remember when Arizona right wing Republicans banned Mexican American Studies. They enforced the law in 2012, forcing administrators to walk into class rooms, during class time, and box up books by some of our most beloved authors, in front of our youth. There were 80+ works on what should have been extolled as the gold standard of Ethnic Studies Courses. This curriculum raised the graduation rate to 98% for the predominantly Mexican American student population of the Tucson Unified School District.

Instead of celebrating our art, history, and culture, reactionary Republicans banned it.

When I and 4 other veteran members of Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say heard about this attack on our familia in Tucson, we were enraged.

If Arizona officials were going to ban our history, we would make more.

We organized the 2012 Librotraficante Caravan to smuggle back into Tucson the books that formed the brilliant Mexican American Studies Curriculum that Arizona right wing Republicans banned.

We mobilized Houston’s Community Cultural Capital, then linked with Communities across Texas to unite with our gente from Arizona. Soon the entire Southwest galvanized, Calfornia, then other states. We united to overturn that racist law.

Each member of our crew had over 10 years experience (at least) organizing our community through Nuestra Palabra. I founded Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say in April of 1998. It would become the first regular Latino reading series in a city where we formed over 45% of the population. Librotraficante High Tech Aztec aka Bryan Parras, Librotraficante Lips Mendez aka Lupe Mendez-recently named Texas Poet Laureate; Librotraficante La Laura aka Laura Razo, and Librotraficante Lilo aka Liana Lopez.

We are approaching the ten year anniversary of the 2012 Librotraficante Caravan, and it is clear that right wing Republicans have re-purposed that attack on our community, our imaginations, our history, our culture. They have changed the details, but the overall attack plan is the same. And this time it has spread.

But we are expert. We are fueling the bus, re-stocking the contraband prose, and alerting all our Librotraficante Under Ground Libraries.

Let us know if you are ready to ride.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Writer, activist, and professor Tony Diaz, El Librotraficante, was the first Chicano to earn a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the University of Houston Creative Writing Program. He earned his bachelor's degree in Communications from De Paul University in Chicago. Diaz is currently a professor of Mexican American Literature and Rhetorical Analysis in Houston, Texas.

From the Field

By Dale Allender, Ph.D.

Original article published here

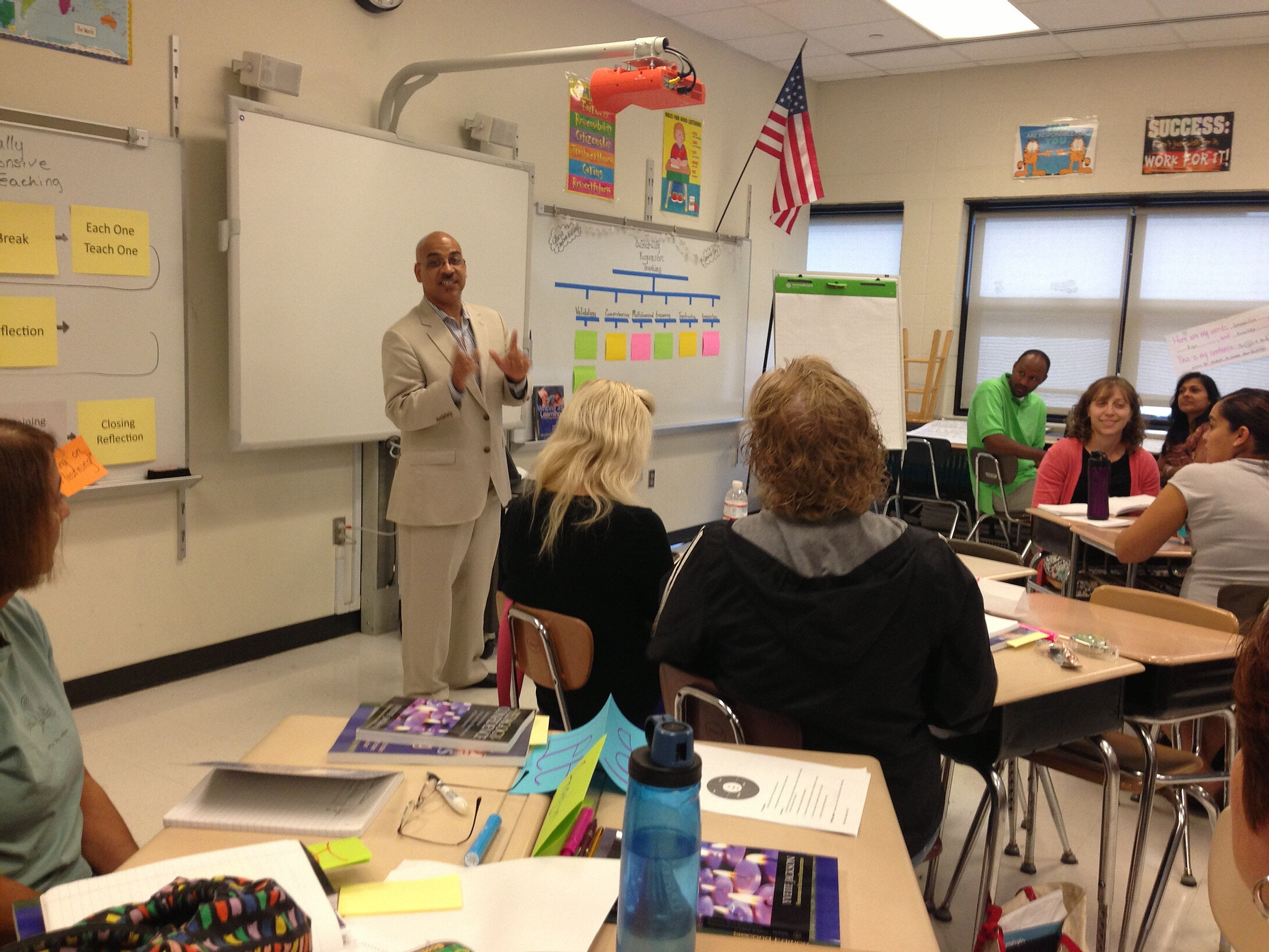

Ethnic Studies Professional Development

After four years, more than 100,000 public comments and three field reviews, the California State Board of Education adopted the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum on March 18, 2021. For districts looking to create and support ethnic studies courses, teacher professional development will be an important element in implementation.

—

Californians have been advocating for ethnic studies at institutional, district and state levels for more than 50 years. More recently, school boards around the state, led by board members such as Rosie Torres in Oakland, AngelAnn Flores in Stockton, and Darrel Woo of Sacramento have been reviewing and passing resolutions supporting ethnic studies and in some cases adding ethnic studies courses as requirements or electives.

And with good reason: research has documented academic and social value for all students taking ethnic studies classes.

As part of my role as co-chair to the curriculum committee of Ethnic Studies Now Sacramento with Drs. Gregory Yee Mark and Margarita Berta Avila; and as co-principal investigator of a U.S. Department of Education Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions (DHSI) grant, I facilitate ethnic studies face-to-face and virtual professional development for school districts throughout California, especially the Sacramento region. With the recent release of California’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum, many more school board members and educators are thinking about ethnic studies in their districts. Below, I’ve provided an outline of the framework our team followed in providing professional development for new and returning cohorts of ethnic studies teachers to help ensure the same valuable experiences and outcomes described in the literature.

Our ethnic studies professional development framework is research-based, historically consistent, culturally sustaining and curriculum-oriented.

Research based. There are many misconceptions about ethnic studies. Ethnic studies does not simply mean adding content about diverse ethnic communities. Ethnic studies is a discipline with a history, a body of knowledge, artistic expression and social positioning. Contemporary studies note that ethnic studies can reduce truancy, decrease dropout rates, and increase grades and test scores across subject matter. Ethnic studies curriculum that generates academic and social value organizes instruction around indigeneity/Native American sovereignty and personal roots; understanding colonization and dehumanization; identifying how communities are marginalized; and exploring community resistance and transformation. Ethnic studies also involves students working to solve problems in their community that they are interested in addressing. For example, in Sacramento, we created Our Stories in Our Voices — the first ethnic studies textbook for high school — over three years, based on successive rounds of feedback from high school students after using the book. California school board members can allocate resources to help train teachers to create and implement ethnic studies experiences consistent with research.

Historically consistent. Ethnic studies was established in 1968 at San Francisco State University and in 1969 at the University of California, Berkeley by African American, Asian American, Chicano/Latino and Native American students and their supporters. Over the years, these very ethnic communities have had to advocate fiercely to not be defunded or restructured out of the curriculum. Therefore, for historical accuracy and to fulfill the original goal and research promise of ethnic studies by ensuring continuous presence of these marginalized ethnic communities, they are named explicitly as focal points for knowledge organization. This does not mean that students should not study their own ethnic heritage if they are not African American, Asian American, Chicano/Latino or Native American. As noted above, personal roots exploration is a necessary component of ethnic studies. What it does mean is that teachers need to be trained to organize their curriculum around the history and culture of these historically marginalized ethnic communities in a research-based ethnic studies survey class.

Culturally sustaining. Four elements of professional development for ethnic studies teachers that make it culturally sustaining are a re-emphasis of the above with a sharper focus. They include indigeneity, immersion, intersectionality and identity.

California indigeneity: While this certainly means the study of California Indians whose communities reside or traditionally resided in the school or district community, it also means land acknowledgement. This can be done by teaching and modeling rituals where we openly acknowledge specific California Indian communities as the original inhabitants of the school community and district land. Additionally, it means researching the indigenous communities originally inhabiting the lands where we live or where we grew up or were born. Lastly, it means understanding settler colonialism and disrupting longstanding curricula that reinforce false narratives, such as units of study about the California Missions or the Gold Rush. Ethnic studies alternatives exist that can be adopted, such as the California Indian Curriculum.

Critical immersion: Immersion in diverse ethnic communities can help build educators’ empathy, knowledge base and solidarity. While ethnic studies educators should not be expected to be experts in all of the ethnic communities studied in a survey class, they should be able to move comfortably into other communities with appropriate cultural humility, inquiry and solidarity.

Personal identity: All ethnic studies teachers should engage in researching and writing their own “critical family history” as part of their professional development, according to education researcher Christine Sleeter. That is a process of first reconstructing family genealogies, geographies and stories; then identifying historic events significant or highly impactful to African Americans, Asian Americans, Chicano/Latinos and Native Americans, first, and ethnic communities second; and finally situating family history within one or more of these events and narrating the points of connection, overlap, conflict or contrast.

Curriculum planning. Teachers need to understand ethnic studies professional development experiences as personal and professional. Professionally, they need time to apply the research-based frames outlined in point number one above to unit plans, lesson plans, and instructional strategies and resources. In our professional development we have adapted this paradigm to the following questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? Where am I? And where am I going? Our Stories in Our Voices organized this paradigm according to the following reading units: Inventing Images, Representing Otherness, Ghosts of the Past, Representing California, and Solidarity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dale Allender, Ph.D. is an associate professor of language and literacy in the Department of Teaching Credentials at California State University, Sacramento where he teaches courses in academic literacy, ethnic studies and racial social justice education.

Intertwined lucha struggle

Given the recent vitriol placed on Critical Race Theory, it is essential to remember that before Critical Race Theory was popularized as an epistemological tool in education, Ethnic Studies was doing the work of centering the narratives of the other, of centering the voices of groups historically minoritized in state curriculum and institutions.

By Izamar D. Ortíz-González,

Ph.D. Student in School Organization & Policy

University of California, Davis

idortizgonzalez@ucdavis.edu

Counterstories

Ricardo Delgado defined a counterstory as an effort by the outgroup to "create its own stories, which circulate within the group as a kind of counter-reality" (1989, p. 2412). Solorzano and Yosso added to the counterstory concept to explain that it serves as an analytical tool to challenge the stories told by those in power (2001). Who's power? The carceral state inherited by the colonizing state, rooted in White Supremacy. At the heart of Critical Race Theory lies the necessity to challenge power and racism by using "experiential experiences" of oppressed groups (Solorzano 1994).

Given the recent vitriol placed on Critical Race Theory, it is essential to remember that before Critical Race Theory was popularized as an epistemological tool in education, Ethnic Studies was doing the work of centering the narratives of the other, of centering the voices of groups historically minoritized in state curriculum and institutions.

The Trenzas, Braids, between Ethnic Studies and The Association of Raza Educators

In October 2020, the Association of Raza Educators (ARE) held their statewide conference virtually for the first time since the statewide grassroots organization started to meet annually. After reciting the land acknowledgment, Lupe Cardona quickly transitioned away to be present, online, at a California state hearing for the off chance she would have to speak in support of state assembly bill 2016, which, if passed, would adapt the ethnic studies the model curriculum she and other Raza educators had toiled to composed months prior. Lupe was a member of ARE and an initial founding member of the Ethnic Studies Now! Campaign in Los Angeles that then became a statewide campaign, and now one of the educators who assembled the Ethnic Studies model curriculum. This intersection demonstrates the linkage between the Association of Raza Educators and Ethnic Studies in California. In the last twenty ten years their history has become interwoven as in a trenza or braid.

Ethnic Studies roots itself as part of the third liberation front initiated with the student activism at San Francisco State University and the University of California, Berkeley. Historically the push for curriculum to include ethnic studies to tell African American, Asian American, Native American, and Chicano studies. In the last ten years, that pressure has emanated from the k-12 students and educators. Part of that push has been fought by educators of the Association of Raza Educators, who have mobilized to push forth ethnic studies as a high school graduation requirement with AB 331. In the last five years, several teachers from ARE and Ethnic Studies Now campaigns have interwoven pushed for the Ethnic Studies high school curriculum and engaged in writing the ethnic studies curriculum.

The history of the Association of Raza Educators (ARE) intertwined with the push for Ethnic Studies. However, its origins were found down south in San Diego in 1994.

Before I continue with this history, I will digress to make a note on nomenclature. "Raza" was initially understood to refer to Mexican-American, south of the border immigrants/. Children of immigrants residing in the united. This name still carries hurt and different meanings for others. In a Statewide leadership meeting of 2020, the term "Raza" officially clarified that RAZA signifies all people oppressed by carceral, colonial, racialized institutions of the United States regardless of socially constructed notions of race.

Spring of 1994 & Proproposition 1994

The idea of ARE came in the Spring of 1994. Ernesto Bustillos was a member of Union del Barrio, a political grassroots organization founded in the Barrio Logan of San Diego as a means to uplift "Raza." As an eighth-grade teacher, Ernesto Bustillos created ARE to unite Raza educators to fight CA Proposition 87. This proposition sought to illegalize public services like health care and public schooling to undocumented families and children of undocumented parents. Despite the fight by community organizers like Union del Barrio and the newly created Association of Raza Educators, people forget that California voters passed the proposition. The judicial system protected undocumented families from the legislation by declaring it unconstitutional.

A.R.E., like the fight for Ethnic Studies, always interviewed in activism in order to push for policy change. Since then, the Association of Raza educators has become a space for educators to address the microaggression and discrimination they face because of their various identities. Congruently, the organization aims to empower students and the community. It does that through the activism push of educational campaigns like Ethnic Studies, the protection of the community against I.C.E. raids, and providing political education to other educators and the community at large. Through A.R.E., teachers carved an alternative learning site to find the political education professional development they do not receive in their school districts, and of course, part of that political education is woven back into Ethnic Studies, the story of us.

The future?

With the passage of ethnic studies as a high school requirement in California, there is hope that the course becomes popularized in primary grades before the high school requirement. However, the recent pushback against C.R.T., although not as profuse in the classrooms as the Right claims, begets us to be cautious. If you wish to learn more about the Association of Raza Educators visit us at razaeducators.org

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Izamar Ortiz-González is a daughter of immigrant parents. This experience thought her to navigate multiple narratives at school and at home. Bridging the gap between these narratives has been her goal throughout her life as a teacher, organizer and student. She double majored in International Relations and Spanish for her BA at UC Davis. She received her single subject teaching credential and Masters of Arts in Education from Loyola Marymount University. She spent six years as a public school teacher in Sacramento, California. She organizes with other educators through the Association of Raza Educators